From Crosses to Crescents: Islamic-Christian Art That Brought the Medieval Mediterranean Together

Yakutiye Madrasa, Erzurum. Central muqarnas, Islamic ornamental three-dimensional architectural decoration, embellishing a church ceiling, 1310. Credit: Richard Piran McClary

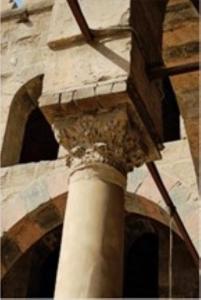

Coptic capital with Christian cross and other symbols at the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad in the Citadel in Cairo. Credit: Sami Luigi De Giosa.

Silk samite with Islamic calligraphy lines the casket of Saints Pelagius and John the Baptist, possibly Iberia, eleventh to early twelfth century. Credit: Museo de San Isidoro, record no. 3-089-002-00.

A new volume reveals that Muslim and Christian art objects fostered peace and coexistence among the coastal communities of the medieval Mediterranean.

SHARJAH, SHARJAH, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, September 15, 2025 /EINPresswire.com/ -- Ceramic vessels originating in the Islamic world once adorned the facades of churches and other Christian monuments, while Christian symbols such as the cross embellished columns, slabs, and other architectural elements in numerous mosques and Islamic monuments.

This was the reality of the Medieval Mediterranean, a vast and vibrant region now explored in a new volume that presents compelling evidence of a historic rendezvous where Islam and Christianity engaged, intermingled, and coexisted through art.

The coexistence across this massive and influential region, spanning the coastal littorals of Europe, Asia, and Africa, was not the result of political or diplomatic rapprochement. Rather, it emerged from the power of art objects, both Muslim and Christian, which fostered cross-cultural dialogue and peaceful exchange.

In Muslim and Arabic jargon, the Mediterranean is referred to as al-Baḥr al-Abyadh al-Mutawassiṭ or the White Middle Sea. Historically, Arabs referred to the sea as Bahr al-rum or Sea of the Romans.

“We wanted to depict the Mediterranean not simply as a land of clash, but as a crossroads where Christianity and Islam met, borrowed ideas, and reshaped each other,” said Dr. Sami L. De Giosa, the volume’s lead editor and an Islamic art and architectural historian at the University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates.

“It is clear from the evidence that this region was alive with goods of all sorts being carried across seas—textiles, metalwork, ceramics. These objects weren’t merely practical; they were signifiers of power, taste, and belonging, and they told stories of dialogue across faiths.”

The 300-page volume, comprising ten chapters, focuses exclusively on Muslim and Christian artifacts that crossed cultural boundaries even when religious doctrines did not. In their introduction, the editors coin the term “aesthetic space” to describe the multicultural role that art objects played in the medieval Mediterranean.

“In a time when the use of the terms Islamic and Christian for art outside the mosque and the church is becoming increasingly difficult, such a space can also be useful in renegotiating how religious and secular are associated,” the editors write.

The volume’s geographical scope includes nearly two dozen countries with Mediterranean coastlines. Its contributors concentrate on finely crafted metalwork, marble, stone, and dazzling textiles – objects admired regardless of their Christian or Muslim origins.

“The medieval Mediterranean wasn’t a neatly divided world of faith. It was a messy, fascinating, interconnected world where communities often recognized more in each other than we might expect,” explained Dr. De Giosa.

“We learned this by paying attention to what people built, touched, wore, and prayed with. These findings remind us that much of our perception about religious difference is, in fact, contemporary and not rooted in history, as traditionalist views often profess.”

One striking example is the presence of a prominent Christian insignia – the cross – on the columns of the mosque of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad in Cairo’s Citadel. Although the columns are historically seen as part of medieval spolia, the volume reconstructs the historical narratives behind these architectural objects to illustrate its central thesis of “aesthetic space.”

Many such architectural objects in the Medieval Mediterranean, one of the volume’s chapters shows, represented a “remarkable transportation” from a Christian to a Muslim cultural and architectural context. The chapter delves into the historical occurrence of Islamic slabs in some of Islam’s most fascinating mosques, presenting them as yet another classic example of Medieval spolia.

For instance, the chapter refers to the Byzantine slabs that were inserted in an imperial mosque in Istanbul. The slabs were originally part of the Hagia Sophia, then moved to the Mausoleum of Ottoman Sultan Sulaiman the Magnificent before their transportation to the mosque.

The volume uncovers both known and lesser-known cases of Christian and Muslim spolia in religious architecture. Though such incorporations may be viewed as sacrilegious by some – Muslims, for instance, traditionally reject the cross – the Christian artifact within a mosque is nonetheless revered within the aesthetic space.

Coptic textiles embroidered with Christian inscriptions, known as tiraz, are presented as examples of the “spoliation of ideas” in the material culture of the medieval Mediterranean. Christians who reprised the style of Islamic tiraz textiles, a luxury medieval Islamic cloth, occasionally transformed them into Christian objects sometimes with Coptic inscriptions.

Most of the volume’s case studies aim to reconstruct the original contexts of such practices through rigorous textual analysis, comparison with material remnants, and impartial interpretation of visual evidence where documentation is lacking.

The volume models the aesthetic space between Christianity and Islam primarily through the transfer of objects across cultural and religious boundaries. This exchange was not one-directional: Muslims incorporated Christian artifacts into their worship and daily lives, just as Christians consumed Islamic goods despite their evident Islamic legacy.

The volume also examines the presence of Islamic ceramic bowls and dishes known as bacini, which were embedded in the facades of Christian monuments in Italy, France, and Germany. Despite their Islamic inscriptions and symbols, these objects were admired and preserved. “The range, variety, and vast geographical extent of the vessels’ point of origin creates its own bacini Mediterranean microhistory,” the volume notes.

Rather than a chasm between faiths, the volume attests to a rich intermingling of Islam and Christianity in the Medieval Mediterranean. Its contributors uncover one piece of evidence after another showing how objects facilitated this cultural dialogue.

The book also explores “hybrid objects” – minute cultural and artistic works that passed through “three hands.” One chapter presents the fascinating story of an Orthodox liturgical object composed of Islamic and Latin elements.

Co-editor Nikolaos Vryzidis of the School of Applied Arts and Culture at the University of West Attica emphasizes that the Mediterranean and its hinterlands were zones of intense contact between diverse religions and languages during the Middle Ages. “They offer a rich array of intercultural contexts, which is an ideal setting for the kind of interdisciplinary inquiry we sought to pursue.”

The intermingling of Christianity and Islam is clearly illustrated in a chapter of the volume where the authors examine the presence of Muslim muqarnas, also known as honeycomb vaulting, in churches located in Anatolia and Mosul, in present-day Iraq. Although neither region borders the Mediterranean coast, the volume considers them as part of its cultural hinterlands.

Muqarnas, three-dimensional Islamic architectural ornaments, appear in Christian contexts and are described by the editors as “a contemporary and boundary-crossing decoration of the time, like so many architectural devices of the past, freely borrowed and imbued with specific meanings in different contexts.”

The contributors to this book show how porous the boundaries of faith and culture were in the medieval Mediterranean, particularly in relation to art and objects. Craftsmen, as the volume shows, followed a kind of “first-come, first-served” logic regardless of the religious connotation of objects.

“They (craftsmen) worked for whoever paid, not for one religion alone. A patron might be Christian, Muslim, or anything else. What mattered was skill, style, and beauty,” said De Giosa. “In the medieval Mediterranean world, art and architecture weren’t guarded as exclusive symbols; they were shared, admired, and repurposed across communities. Another important aspect is our focus on lesser-known, neglected case studies.”

The volume presents a captivating array of micro-historical case studies in which two of the world’s largest religions, Islam and Christianity, meet, engage, and intermingle during a historical epoch from which both faiths, still the world’s majority religions, can now draw meaningful lessons.

“In relation to our volume, the appeal of its case studies is almost self-evident,” the editors write, noting that the political turbulences following the 9/11 attacks, including the subsequent wars, events, and upheavals, have sparked significant academic interest in historical studies that explore the

confrontation or coexistence of Islam and Christianity.

LEON BARKHO

University Of Sharjah

+971 50 165 4376

email us here

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.